12 Dec 2024

10 MIN READ

COP29 - The $300 Billion Act of Tokenism?

Since the 1990s, climate change has been a crucible of contention in the global community, with nations entangled in fraught negotiations and heated debates. These efforts have resulted in landmark agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement, and now the tumultuous $300 billion COP29 deal aimed at addressing the implications of climate change. Like many international negotiations, this agreement has elicited mixed reactions from delegates worldwide. Yet, while the latest pledge aspires to address the escalating climate crisis, it starkly reflects a troubling pattern of tokenism in global climate diplomacy. Critics argue that such agreements, though symbolically significant, often lack the scale, urgency, and equitable action needed to confront the crisis effectively. COP29 will be remembered for its controversial $300 billion deal, finalised when most delegates at the talks were already on flights back home.

The 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) concluded with a climate finance pledge. The cornerstone of the new agreement is the commitment to mobilise at least $300 billion annually by 2035 to support climate action in developing countries. This goal, a step up from the previous $100 billion target, is part of a broader ambition to scale climate financing to $1.3 trillion by 2035. The funding is expected to come from both public and private sources, strategically leveraged through public financial instruments. The new financial commitments aim to accelerate global efforts for climate adaptation, mitigation, and resilience, particularly supporting the least-developed nations and small island states.

While some hailed the COP29 summit as progress, others, particularly representatives from developing nations, criticised it as an act of tokenism, suggesting that the agreement is a symbolic commitment that overshadows substantive progress. Several stakeholders criticised it, arguing that it did not adequately address the current climate needs of developing countries or align with scientific recommendations. Subsequently, the walkout by frustrated delegates raised concerns about the summit’s integrity and procedural fairness. With the world on the brink of climate catastrophe, It’s worth questioning whether this pledge represents a genuine breakthrough or if it's all smoke and mirrors.

The Legacy of Missed Climate Deadlines

As COP29 commenced, the head of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), a U.N. agency responsible for monitoring weather, climate, and water resources, issued a stark warning to journalists in Baku. Declaring that the planet is on "red alert," he highlighted that 2024 has officially been the hottest year on record, emphasising the urgency of the situation. The scientific community is increasingly alarmed about the rapid acceleration of climate change, with evidence indicating that global warming is advancing faster than current efforts to mitigate it. What was once a hypothetical concern is now an undeniable reality, with its impacts being felt worldwide—most acutely by nations vulnerable to environmental shifts.

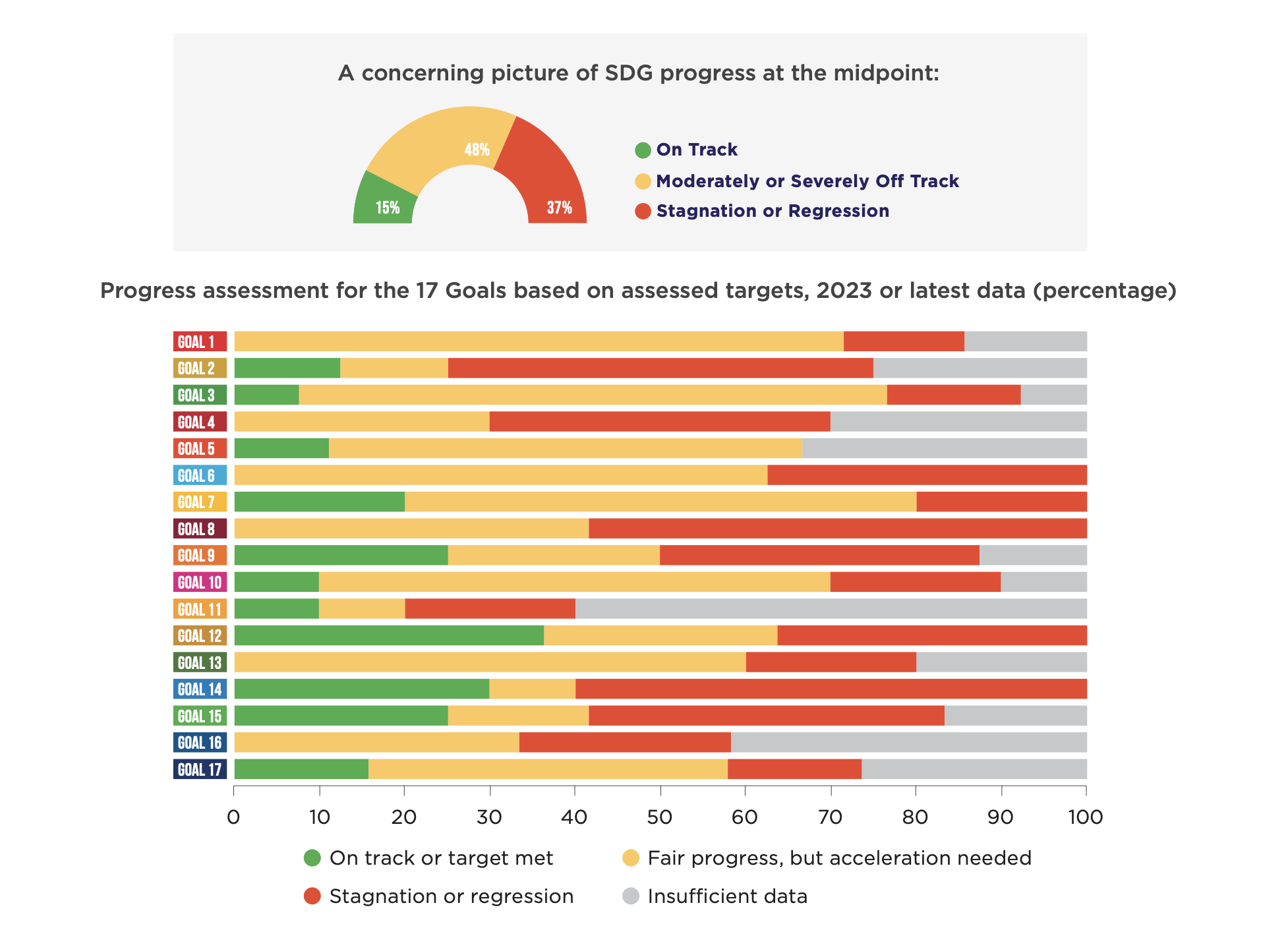

The sustainable development goals progress chart 2023. Source https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/progress-chart/

This growing alarm is rooted in the stark realities of our planet's warming trajectory. Scientific data, such as ice core analyses, reveal that this increase surpasses anything seen in the past 800,000 years. Such warming is already causing devastating effects, including rising sea levels, extreme heat waves, droughts, storms and cyclones and widespread ecological degradation. With each passing year, the time to reverse or even mitigate these impacts dwindles. At its core, the fight against climate change is a race against time, Yet, despite the overwhelming scientific evidence and the pressing nature of this crisis, the collective response of global leaders and lawmakers remains painfully inadequate.

This inadequacy was sharply criticised by Indian delegate Chandni Raina at the close of the summit. She pointed out the failure to address both the financial and systemic magnitude of the crisis. "I regret to say that this document is nothing more than an optical illusion," she remarked moments after the agreement was finalised. "This, in our opinion, will not address the enormity of the challenge we all face. Therefore, we oppose the adoption of this document."

While some voiced strong opposition to the summit's outcomes, others sought to highlight its merits and potential. UN chief Simon Stiell acknowledged the complexity of the negotiations and praised the outcome, calling it "an insurance policy for humanity against global warming." However, he also cautioned, "Like any insurance policy, it only works if the premiums are paid in full and on time."

Simon Stiell addresses the closing plenary of COP29 in Baku and waves a copy of the Paris Agreement. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/unfccc/albums/

Though the analogy is compelling, it feels misplaced given the history of missed climate commitments. Consider the track record: at the 2009 UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen (COP15), developed countries committed to mobilizing $100 billion annually by 2020 to support developing nations in combating climate change. The Paris Agreement reaffirmed this target and extended the commitment to 2025 while stipulating that future financial goals should be determined based on the needs and priorities of developing countries. Despite the pledge, the $100 billion target was not met by the 2020 deadline. It was only achieved in 2023, three years later, as reported by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), illustrating a pattern of overdue premiums.

Delayed climate action comes with a cost, one that compounds over time. While countries continue to negotiate and miss deadlines, the crisis grows more urgent. The pressing question remains: Will the $300 billion target set at COP29 follow the same pattern?

Climate Finance Gap: $300 Billion vs. $1.3 Trillion

The key issue of the $300 billion COP29 deal lies in the inadequacy of the pledged amount compared to the expectations of developing nations. Wealthy countries, the primary historical contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, have committed to providing $300 billion annually by 2035—far less than the $1.3 trillion sought by developing nations. Experts have emphasized that this higher figure is crucial to address climate challenges effectively as this figure aims to support both mitigation efforts (reducing emissions) and adaptation strategies (addressing climate change impacts). According to the World Resources Institute, $1.3 trillion per year is required to transition to clean energy, build resilient infrastructure, and address loss and damage caused by climate change.

World’s average temperature against pledges for 2030 and beyond according to the Climate Action Tracker. Source: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/paris-global-climate-change-agreements

According to the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance, developing countries require approximately $1 trillion in external climate finance annually by 2030, increasing to $1.3 trillion by 2035. Of this, around $500 billion annually should come from public funding, while the remainder would need to be mobilized from private sources. Public finance instruments, such as guarantees or co-investments, are essential to reduce risks and attract private investment in emerging markets and technologies. While the COP29 finance deal’s $300 billion annual commitment by 2035 marks an increase over previous pledges, it falls dramatically short of the estimated $1.3 trillion needed annually. The proposed $300 billion fund represents only a fraction of what is needed and highlights a significant funding gap. Furthering concerns about the gap between Climate change and Climate action.

This stark funding gap has frustrated developing countries. Representatives from Least Developed Countries (LDCs), small island developing states (SIDS), and vulnerable states staged walkouts at COP29, denouncing the $300 billion pledge as grossly insufficient. Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu's envoy, lamented that past experience suggests these promises are rarely fulfilled. All in all, COP29 highlights the divide between wealthy emitters and those bearing the brunt of climate impacts.

The Unpacking the $300 Billion Deal

In climate finance, adaptation and loss and damage (L&D) funds are essential components aimed at addressing the negative impacts of climate change, particularly for vulnerable countries. Adaptation funds are intended to help countries, especially in the Global South, adjust to climate change impacts. These funds are directed toward building resilience, improving infrastructure, and implementing climate-resilient development strategies to cope with the changing environment. On the other hand, loss and damage funds focus on addressing the irreversible consequences of climate change—those impacts so severe that they cannot be avoided through adaptation, such as extreme weather events and rising sea levels. These funds aim to provide financial support to countries suffering from these catastrophic impacts, assisting with recovery and mitigation efforts.

Developing countries face a significant shortfall in adaptation funding, with an estimated gap ranging between $194 billion and $366 billion annually. As Obed Koringo, climate policy adviser at CARE International, emphasized, "Adaptation is an essential lifeline for vulnerable communities, yet the Global Goal on Adaptation still lacks the crucial means of implementation." This lack of adequate funding poses a severe challenge, particularly for the most vulnerable nations, where equitable distribution and favourable terms are critical for their survival. Furthermore, there is a continued reliance on unsustainable debt structures, which must be addressed for long-term viability. Despite the urgency, the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) lacks measurable "means of implementation," with negotiators debating whether to use quantifiable indicators or broader "enablers" such as governance and transparency. Negotiators were meant to make further progress at COP29 by selecting indicators, but discussions were derailed. While a technical workshop planned for 2025 aims to develop adaptation indicators, the need for actionable, measurable support is urgent. The current systems often exacerbate inequalities by imposing lengthy processes and conditions that delay the delivery of critical support.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres addressing the High-Level Dialogue on Loss and Damage at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/unfccc/albums/

The issue of loss and damage was a central focus at COP29, with the Loss and Damage Fund being fully operationalized during the summit. Originally established at COP27, the fund is designed to assist developing countries, especially those most vulnerable to climate impacts, in addressing both economic and non-economic losses. In addition, the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage (WIM) was reviewed at COP29, emphasizing coordination and complementarity between the new fund and existing climate policies. This review was crucial for streamlining the relationship between new funding mechanisms and ongoing climate actions under the Paris Agreement.

While pledges to the Loss and Damage Fund have increased, reaching $759.4 million, concerns persist regarding the adequacy of these funds given the scale of losses expected by 2030, estimated at $580 billion annually. Critics, particularly from the Global South, argue that these financial commitments remain insufficient to meet the urgent needs of climate-vulnerable communities. As Koringo stated, "COP29 has failed to address developing countries’ pressing climate change needs. Pledges remain insufficient more than a year after the creation of the loss and damage fund. Climate-vulnerable communities cannot endure further delays—delivering meaningful funding is not just an act of solidarity; it is both a moral and practical necessity." Despite an $85 million increase in pledges to the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD), the total amount raised remains a fraction of the $580 billion in annual losses expected by 2030, highlighting the disparity between pledged funds and the enormity of the challenge.

Inequity in Climate Finance Commitments

The principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR) has been a cornerstone of global climate negotiations since its establishment in 1992 at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro. At the heart of the CBDR principle lies a recognition that countries contribute differently to the climate crisis. Wealthier nations, having historically emitted the most greenhouse gases, bear greater responsibility for mitigation and financial support. Yet, current climate finance commitments continue to fall short of addressing the needs of developing nations.

Indian negotiator Chandni Raina recently pointed out a critical gap, stating that the $300 billion climate finance pledge “does not address the needs and priorities of developing countries.” She noted that this amount is incompatible with the principle of CBDR, particularly as it avoids concrete demands such as region-specific targets, income-based allocations, or adaptation-focused spending. Furthering the belief that the lack of concrete and targeted actions suggests token gestures rather than a substantial step toward global climate equity.

Civil Society Actions around the COP29 venue in Baku Azerbaijan, 2024. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/unfccc/albums/

First, there is a growing call for other wealthy nations, such as emerging economies with higher economic capacities like China, and oil-rich Gulf states, to also contribute significantly to climate finance. Although these nations are not typically bound by the same obligations as developed countries, there is increasing recognition of their wealth and emissions profiles, which make them capable of stepping up their contributions. Some of these nations already contribute to climate action initiatives in developing countries, often through multilateral financial institutions like the Green Climate Fund. Yet, there is a need for more transparent and consistent contributions from these countries to meet the global climate finance goals.

Secondly, research from the World Resources Institute (WRI) has shown that developed countries, including the United States, Australia, and Canada, are not meeting their fair share of climate financing based on their economic size and historical emissions. While developing countries are encouraged to participate in climate financing, their obligations remain more flexible. Still, the principle of CBDR ensures that the primary burden of financing falls on the wealthier nations with the greatest historical responsibility and the capacity to contribute.

Lastly, wealthy nations, many of which have historically been the largest emitters of greenhouse gases, have cited domestic budget constraints and rising geopolitical tensions as reasons for not making more substantial financial commitments to combat climate change. Critics argue that these justifications do not address the scale of the crisis or the responsibilities these nations bear in supporting global efforts. Furthermore, geopolitical conflicts, such as Russia’s war in Ukraine and escalating tensions in the Middle East, have not only overshadowed the climate issue but have also directly contributed to rising carbon emissions. Interestingly, these same nations continue to subsidize fossil fuel industries, undermining their commitments to international climate agreements. As a result, climate change concerns have slipped down national agendas, as crises like geopolitical unrest and economic instability, fueled by rising inflation, demand more immediate attention. Consequently, the urgency to mitigate global warming has been deprioritized, despite the growing need for decisive action.

Overall, these elements demonstrate a pattern of tokenistic actions, where countries make pledges or acknowledge the climate crisis but fail to enact the necessary policy changes or provide sufficient financial support to meet the urgent needs of developing countries. Tokenism becomes evident when actions lack the depth, specificity, and urgency needed to address systemic climate inequities.

Equity Struggles: Climate Finance Framework Fails Developing Countries

Beyond the financial shortfalls, COP29 negotiations exposed the deep structural inequalities inherent in the climate negotiation process. Among the summit’s key outcomes was a historic call for countries to move away from fossil fuels, accompanied by ambitious targets to expand renewable energy, reduce transport emissions, and protect forests. However, the world’s poorest and most vulnerable nations emphasized that the allocation of finance for making these adaptations remains a critical issue. The deal reached on Sunday failed to provide concrete steps for implementing last year’s pledge made at the UN climate summit to transition away from fossil fuels and triple renewable energy capacity this decade. Some negotiators pointed out that Saudi Arabia had actively tried to block this plan during discussions.

The negotiations at COP29 also highlighted a troubling power imbalance, with fossil fuel-producing nations working to weaken the agreement and suppress the voices of vulnerable countries. Saudi negotiators emerged as key opponents, resisting not only proposed provisions on carbon emission cuts but also opposing measures on adaptation, national climate pledge registries, and more. Alden Meyer from the think tank E3G described their actions as “a wrecking ball,” suggesting that they may have been emboldened by political shifts, such as Donald Trump’s electoral victory.

Raina brought attention to these inequalities, criticizing not only the insufficient financial commitments but also procedural issues. She revealed that the Indian delegation was denied an opportunity to speak before the deal was adopted—an incident emblematic of the systemic power imbalances dominating climate talks. This sentiment of exclusion was echoed by delegates from Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS), many of whom felt sidelined throughout the negotiation process.

Chandni Raina of India as she speaks during a closing plenary meeting at COP29 in Baku. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/unfccc/albums/

In an unprecedented act of protest, delegations from these vulnerable nations staged a collective walkout, condemning the lack of meaningful engagement with their concerns. The LDC negotiating bloc, representing 45 nations and over 1.1 billion people, issued a scathing statement describing how years of effort to establish a robust climate finance framework had been effectively dismantled in the final agreement. “Despite exhaustive attempts to collaborate with key players, our appeals were met with indifference,” the LDC group stated. “This casual dismissal not only erodes the fragile trust that sustains these negotiations but also mocks the very spirit of global solidarity.”

Reflections

For these nations, whose survival depends on immediate action, such gestures feel more like mockery than meaningful support. Juan Carlos Monterrey Gómez, Panama’s chief negotiator, strongly criticised the process leading up to the final agreement. He stated, “This is what they always do. They break us at the last minute. You know, they push it and push it and push it until our negotiators leave. Until we’re tired, until we’re delusional from not eating, from not sleeping,” he told Al Jazeera. Delegates were displeased with the way the agreement was adopted and Chandni Raina the process was “stage-managed”.

While global climate efforts and funding have increased over the years, the disparity between ambition and impact remains glaring. The progress is commendable. However, the world is experiencing climate change disproportionately, and this disparity is mirrored in the global response. Vulnerable nations face ecological collapse, with some already on the brink of becoming uninhabitable. This reality signals why many perceive current efforts as tokenistic—symbolic gestures that fail to meet the gravity of the crisis.

As the world turns its attention to COP30 in Belém, Brazil, it remains clear that without a substantial increase in financial commitments and a more inclusive, equitable negotiation process, the global community will continue to fall short in the fight against climate change. Without urgent, decisive action, the goals of the Paris Agreement and the promises made in Baku will remain distant dreams rather than the transformative milestones needed to secure a livable future for all. COP29 has left the world at a crossroads, with the window for meaningful action rapidly closing. The stakes could not be higher.

Sources:

- Key takeaways from COP29: a contentious finance deal, carbon markets, more

(https://www.esgdive.com/news/key-takeaways-from-cop29-a-contentious-deal-carbon-markets-more/734082/#:~:text=The%20final%20COP29%20finance%20deal,least”%20%24300%20billion%20per%20year.) - Developing nations blast 300 billion USD COP29 climate deal as insufficient

(https://www.onmanorama.com/lifestyle/news/2024/11/25/cop29-summit-developing-nations-300-billion-dollars.html) - COP29 ends in $300 billion deal, widespread dismay — and eyes toward COP30

(https://news.mongabay.com/2024/11/cop29-ends-in-300-billion-deal-widespread-dismay-and-eyes-toward-cop30/) - Developing nations blast $300 billion COP29 climate deal as insufficient

(https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/sustainable-finance-reporting/wealthy-countries-back-raising-cop29-climate-deal-300-billion-sources-say-2024-11-23/) - Key aspects of the Paris Agreement

(https://unfccc.int/most-requested/key-aspects-of-the-paris-agreement) - Failures and Successes of Paris Agreement

(https://ace-usa.org/blog/research/research-foreignpolicy/failures-and-successes-of-the-paris-agreement/#:\~:text=Despite facing setbacks and failures,historical context and political perspectives.) - Getting a New Climate Finance Deal this Week Hinges on 3 Elements

(https://www.wri.org/insights/ncqg-climate-finance-negotiations-cop29) - Key Outcomes from COP29: Unpacking the New Global Climate Finance Goal and Beyond

(https://www.wri.org/insights/cop29-outcomes-next-steps) - The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

(https://www.ipcc.ch) - Global Climate Agreements: Successes and Failures [Overview and History]

(https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/paris-global-climate-change-agreements)